Jane MacGill , W.L.A., helping with the harvest near North Berwick.

The Women’s Land Army

On the 9th October 2012 the Duke of Rothesay (Prince Charles) unveiled a memorial to the Women’s Land Army at Clochan, near Buckie, in Moray. The fact that this was the first such memorial in the UK is a potent statement regarding the lack of recognition the WLA has had in the years since 1945. It is, perhaps, a powerful comment on the perception of what merits official recognition and in that ‘contest’ the rifle is only slowly relenting its pre-eminence to such as the hoe.

In the 1940s the country was self evidently at the mercy of the farming industry’s inability to produce sufficient quantities of food to feed the whole population. As the months of the war grew to years, the British people would have suffered considerably more from developing food shortages than it did, had the Government not resorted to rationing and, further, had it not taken steps to replace male farm workers who had gone to the armed forces with female labour.

The Women’s Land Army, first raised during the First World War, was reborn in June 1939. At first volunteers filled the places but later numbers were considerably increased via conscription. The women were needed by an industry still essentially labour intensive and, given East Lothian’s overriding rural character, the W.L.A. was employed in considerable numbers in the county.

The experience the members of the W.L.A. had of their wartime work varies from the fond and faintly wistful to the kind mild ‘amnesia’ brings on through unpleasant memories. For many, especially those reared in towns, who found themselves sent alone or in small numbers to the more remote farms, it was all a bit of a lonely shock and the process of learning the ropes an exhausting and difficult experience. Those sent to live in larger billets, like Quarry Court near North Berwick or Saltoun Hall, were at least able to cry on the shoulders of room mates similarly learning to move to new rhythms and running on new tracks.

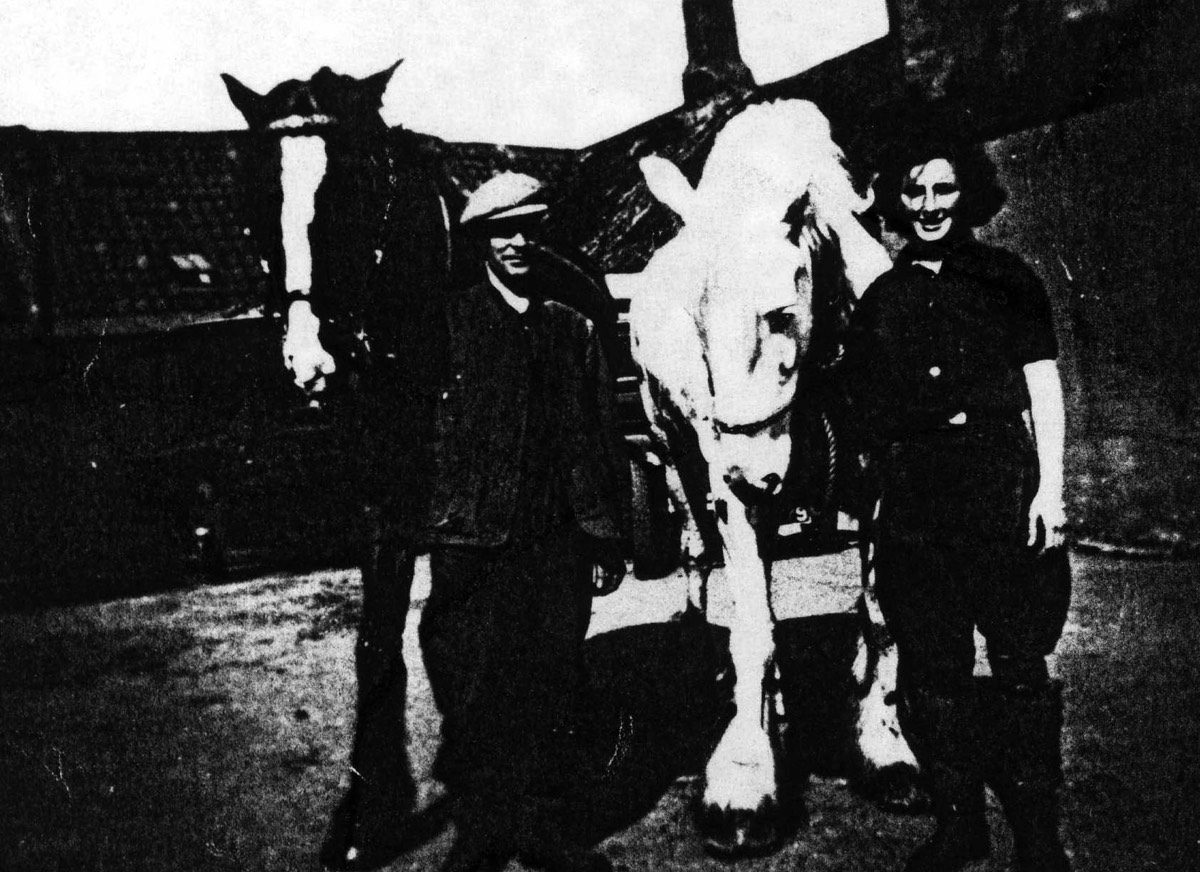

Hours were long and rising came early. Mud, earth and grit, rain and sunshine, wind, ice, and snow all did their best to leave their marks on young faces and the physically demanding work toned muscles slowly and often painfully. The east coast haar brought chill winds to open fields as much as the sun brought welcome days of bearable enjoyment. While many Land Girls did come in time to drive tractors in ploughing, harrowing and such like, some began their learning by helping with horses, whether the teams for ploughing or the gentle (or none too gentle) Clydesdale used simply for pulling a cart of turnips or dung. While the men did most of the skilled work with horses or machinery, a Land Girl did pretty well whatever job had to be done on the farm.

Land Girls lifting turnips near Whitekirk.

Harvest home at Saltoun thanks to the combined efforts of the army, the farm workers and six Land Girls.

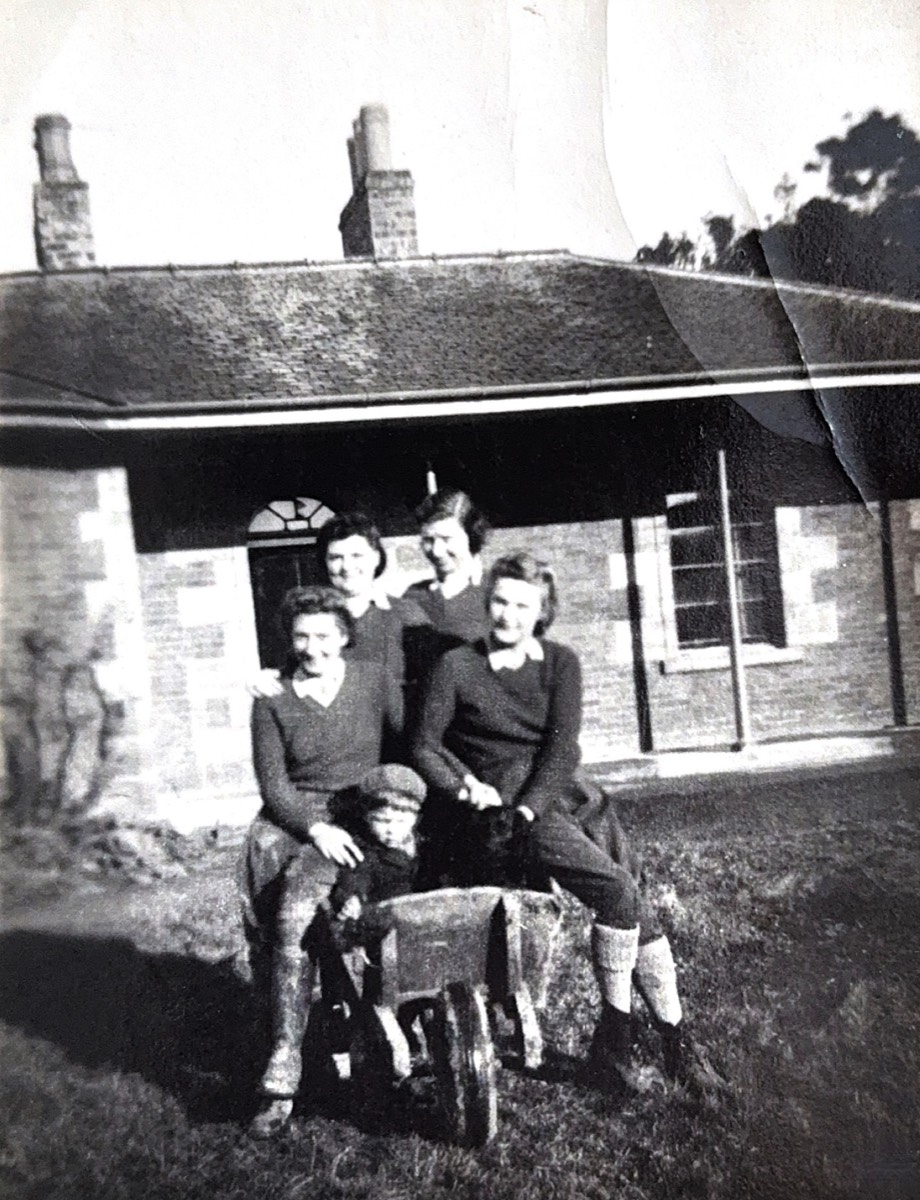

Land Girls photographed at the hostel at Quarry Court, North Berwick.

Jane MacGill, pictured above is third from the left.

Eyewitness - Catherine Cameron, Edinburgh, September 1998

Cathy S. Cameron describes her experiences in the Women’s Land Army in East Lothian, 1943-46. She shared her work at Saltoun Hall, Pencaitland, with other members of the W.L.A. like Ella Ritchie, Mary Hutchinson, Doris McAlister and Betty Treherne. She wrote:

“The work was hard, often back-breaking and dirty, the hours were long, the pay was poor, the holidays were one week per year and there was a war on. It was the happiest time of my life!

In the Spring of 1943 my friend and I went by S.M.T. bus to a large mansion-house in East Lothian which was to be our home for three years whilst serving in the Women’s Land Army. There were another five girls there, three of whom worked in the market gardens, and we had very comfortable accommodation, including our own sitting-room with wireless and listening to ITMA was a must, as was dancing to Victor Silvester and his Ballroom Orchestra. Usually we were in bed by 8.30, oblivious until 5.30 next morning. We had our own, excellent cook and all met at mealtimes when the day’s gossip was exchanged – there was always some! Christmas Day was an ordinary working day though we did have a turkey and wine dinner; the rest of the year we had ordinary civilian rations.

The four of us who worked on the farm, to begin with feeling a bit strange in dungarees and boots, etc., gradually got used to the outdoor life, from potato planting right through to the winter chores. When planting and picking potatoes we wore a ‘brat’, a kind of apron made of coarse sacking in which we carried the spuds. It could be very hot in the fields in summer and I got someone in Haddington to make me an ‘ugly’ – the old-style cotton sunbonnet – which proved to be a good protection from heat and dust. I sometimes wish that I had a photograph of myself wearing it but, on second thoughts, better left to the imagination! We sang a lot and I shall always associate ‘The Bonnie Earl of Moray’ with singlin’ neeps! One day three Irish workers were cutting hedges (if they spoke it wasn’t in English) and I had to walk behind them with a Scaffie’s brush sweeping the road (“what did you do in the war, Auntie?”).

Haymaking was followed by harvest, the busiest time of all. These were still the days of the reaper and binder and our job was to gather the sheaves and stand them on end, eight to a stook. Wheat was much heavier than oats but the villain of the peace was the barley awn – to get one in the eye was very painful. Eventually the grain was dry enough for ‘leading in’. These were the golden days, with over thirty workers in one field. The sheaves were loaded on to horse-drawn carts, or uninteresting tractor-drawn trailers, and brought to the corner of the field to be built into stacks. We forked the sheaves to the stacker and one time I too-energetically tossed a sheaf which landed full force on his arm; his only comment was, “eh lassie, that was my dirlie bane”! (funny bone).

In the afternoons cheese or Spam pieces and tea were brought to the field and we all flopped down and enjoyed the break, before once again working on and on and on. Nowadays, when I see a solitary Combine Harvester in a field I think, well, that may be progress but how stale, no comradeship, no teamwork, no laughter. The girls always had to wander off, hopefully to find some bushes to get behind for a few vital minutes! A ‘Harvest Home’ was held in the big house for everyone who had been involved and this was a great event. We used to cycle to kirns at neighbouring farms. These were boisterous barn dances to celebrate the end of harvest and we always hoped there would be moonlight to show us the road home.

Some of our troops helped at the harvest and I especially remember two who were born comedians; they delighted in inflicting ‘tortures’, such as suddenly throwing us into a bed of nettles! At our last harvest there were German prisoners-of-war who came daily from Haddington. They were very thorough and tidy in their work, and made lovely toys from pieces of wood and bits of string, which they bartered for cigarettes. October, my favourite month, meant tattie howkin’ – not my favourite job!

Land Girls at their lunch on Balgone Barns Farm, south of North Berwick.

Very wet, dreich days would find us under cover, either mending sacks or whitewashing byres. This was our only contact with the cattle, apart from occasionally scrounging a jar of their treacle, to augment my jam ration. This was strong stuff but, spread sparingly, didn’t seem to do me any harm. None of us had a watch and, in winter, when working in a distant field, we carried on till the first stars appeared, then we knew it was lowsing time. Early Spring we would be muck-spreading (we had a slightly different name for it), heralding once again the age-old cycle of seed-time to harvest.

Any aches or pains were soon forgotten at the Friday night dances in the village hall. These were great fun, with a very good band from the Tranent area. They weren’t exactly genteel affairs and as they went on till two in the morning, it was definitely the survival of the fittest. Saturday morning we would just about manage, very bleary-eyed, to clean out the henhouses. Often we went home at weekends – to catch up on sleep! When a nearby, very small village ran a dance there was always the ‘Lancers’ on the programme. This has always puzzled me as it was never danced anywhere else in the district.

Through time we made friends with neighbouring families and I recall wonderful evenings in farmhouses, with lovely home-made food and good old-fashioned party games. We also enjoyed, and appreciated, being welcomed into village homes for fireside chats, homes from whence sons and daughters had gone to the Forces, some, alas, never to return. At a local wedding the bridal couple were presented with a ‘potty’ full of salt as a symbol of good fortune – I hoped it proved to be so. Some of us had our 21st birthdays and, despite rationing, our mothers always managed to provide a cake for the occasion; we would invite some of the local lads to share in the celebrations.

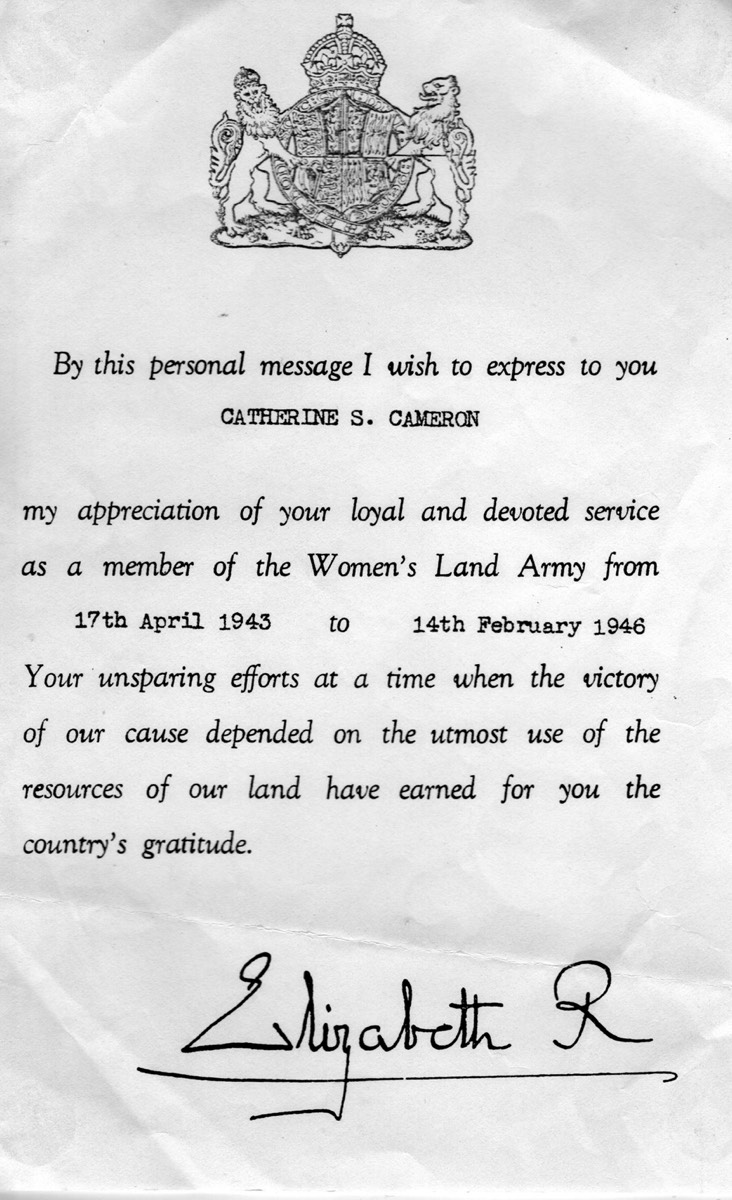

Our numbers gradually dwindled and by 1945 there were only three Land Girls left. We took part in the Victory Parade in Haddington and it was thrilling to march behind a pipe band. The winter of 1946 was when we left the Land Army. The other two girls were getting married and I returned to my office job, so, very abruptly, those happy, carefree days were over. No gratuities or demob clothes for us, just our bus fare home and even that wasn’t right - I had to fork out six pence to make up the difference! Some items of uniform had to be returned and these we took, very appropriately, to a room beside the Funeral Department of the Co-op in Semple Street – the end indeed!

In many ways the Land Army was the Cinderella of the womens’ wartime services but I wouldn’t have changed places with anyone and shall always cherish the memories of those three years in the W.L.A. It all happened over forty years ago – or was it only yesterday?

[C.S. Cameron – 1989]

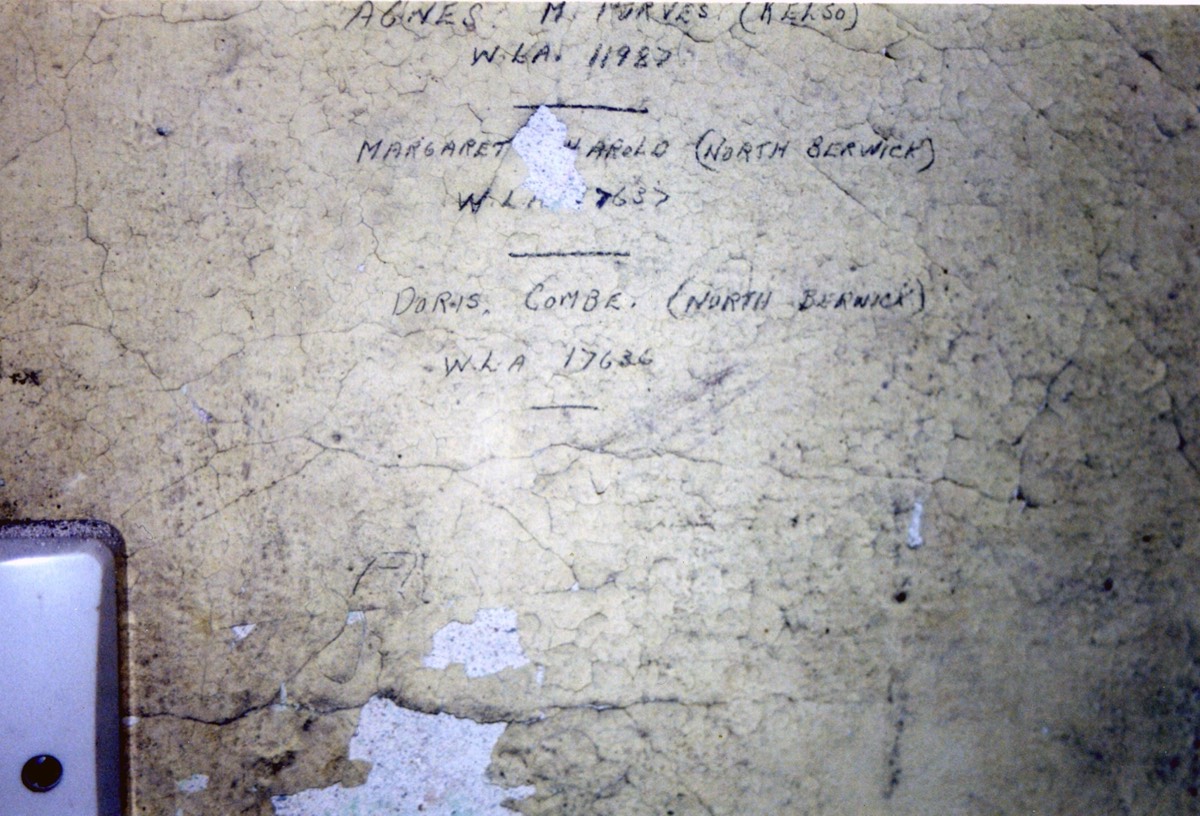

Catherine was one of a group of five former WLA girls who, in 1998, re-visited Saltoun Hall where they had been based during the war. She later wrote:

“It was strange being back at Saltoun Hall and seeing that lovely garden for the first time... The basement gave me the shivers - when I think of all the life that used to be there... My best friend and I shared a room in Saltoun Hall for three years. She married locally and died three years later and is buried in East Saltoun cemetery, so the whole district has bitter-sweet memories for me.”

Cathy Cameron: Marnie Hutchinson: Ellen Ritchie: Betty Treharne; Doris McAllister.

Telling their story in the garden of Saltoun Hall.

Searching for their signatures in the basement.

Margaret and Doris’s signatures on the basement wall, Saltoun Hall, some fifty-four years later.

The third signiture

Agnes Purves from Kelso pictured below Saltoun Hall in 1942

[Courtesy of her Granddaughter, Louise Hunter]

The above photograph shows Agnes Purves on the left and her friends Ann, Janet and Gina to her left.

Eyewitness - Martha Hanlon described her experiences in the W.L.A.:

“I left school when I was fourteen years old and went to work in a shop. I had a love of country life and of animals and when I was sixteen in 1942 I enrolled in the Womens Land Army and was sent for three months training to Crieff on all sorts of different farms.I was then sent to North Berwick to stay at a hostel called Quarry Court. Around fifty W.L.A. girls stayed there and it was a fabulous place, right on the waterfront. My experiences there changed my life because there were so many girls, all so different, and we had such fun. We had a super matron, the food was very good and we even had lunches which we could make up to take away with us. There was always a rush to get the nicest filling!

I worked on several farms whenever help was needed. The farmer would ring up the hostel and ask for however many he needed depending upon whether it was harvest time, lifting potatoes, turnip topping, spreading dung or whatever. We worked from eight am till five pm but in the summers we were very busy and often worked till it was too dark to see. We only worked Monday to Friday and had the week-ends to ourselves. Sometimes we went home at the weekend but our life at the hostel was better as there were always some whose homes were too far away to go home.

We went to dances which were great. No drink was allowed and the ladies lined up on one side and the men on the other and you waited to see who would come for you. There were plenty of fellows as we had the army, the air force and the navy to choose from. The locals had a lot of competition for the girls and we walked everywhere in groups singing and laughing as we went along. Christmas and New Year were spent at home but on some evenings we used to sit around the piano in Quarry Court and the Matron would play for us while we sang. We all loved her.

Land Girls at harvest time in East Lothian.

I was sent to a super farm, a pig farm, and I loved the squeaky, little piglets. On one occasion I was painting the walls with creosote and I fell off the ladder and got so covered in the stuff that I had to go home and take a hot bath. My hair smelt like tar for weeks!

Most of the farmers were very good to us and while some of the women who worked on the farms looked down on us and scoffed us as 'Townies', most were fine once they got to know us. My family thought I was great for going into the Land Army and how I loved all the work, dirty and hard, whatever. On the cold mornings you just got on with it.

I left the W.L.A. after three years as the hostel closed and I went to Leeds to an orphanage but that was so sad and terrible that I left after six months and went to work as a kitchen-maid and then a house-maid. What a laugh this was but I got homesick for Bonnie Scotland and came back north to rejoin the W.L.A.. This time I was sent to Penicuik, to the Glencorse Hotel and went to work at Lambie's at Pomathorn. I was one of the family there: they were the best. I learnt to drive and would drive the girls to work.

I think we did make a contribution to the war effort. We certainly did our best. The best was the wonderful friends I made as there was lots of fun along with the hard work. The worst was the bad weather days but we always had some work to do even in the rain and on the frosty mornings. It wasn't all trouble free as I did turn the car over once on black ice and had a cow stand on my foot and break my toe. I met my husband-to-be in Howgate and left the W.L.A. to emigrate to New Zealand.

Helping with the horses on an East Lothian farm.

Eyewitness - Isa Rankin: Womens Land Army Member, 1940-43

“I trained as a Map Colourist before the war and joined the W.L.A. when I was seventeen in 1940. I was attracted by the open air and because it meant I could work near home. My family was very pleased that I wasn’t going to join the Forces. We didn’t receive any training and were sent to work on a number of places in East Lothian: in the market garden in Haddington, on a farm by Pencaitland and even in the garden of the small hostel where around a dozen of us stayed in North Berwick. We worked from seven am until five pm except when it was harvest time when we worked till nine pm or later. We did general farm work though not with animals: that was mens’ work. I remember stacking bags of vegetables on a lorry destined for Edinburgh market. We got to our work on the open back of an old coal lorry with a metal floor to sit on. Since we were often soaked by the rain or snow I complained and we got a canvas roof after that.We spent a lot of our time off sleeping ready for the next day’s work but for the weekends we sometimes went home for one and a half or two days. When we did we had to get up at four thirty am to enable us to travel to work on a Monday at seven am. In the evenings we just chatted after our dinner but we sometimes had an invitation to a nearby Sergeants’ Mess where there was dancing with airmen and women. We all got on very well together. Food in the hostel was pretty scarce at first and it was later alleged that our warden was found to have been keeping back rations for her own use. Then she disappeared and we had a lovely person to look after us and we were very well fed after that. We were paid twenty-one shillings a week which rose later to twenty-four and we got on OK with our employer. The locals were fine but we mostly kept to ourselves.

I left the W.L.A. in 1943 to train as a nursery nurse and the Land Army Benevolent Fund paid out our expenses for the training period as the ‘salary’ then was £5 per month. The LABF gave us another £5 per month for two years. I think the Land Army made a very positive contribution to the war effort but I don’t think it ever got the recognition it deserved. We weren’t even issued with underwear, only outerwear, and we didn’t receive anything at the end of the war, money or otherwise. I thought the best side of the work was the camaraderie in the hostel and the worst was the winter weather. In addition we were expected to do heavier work than the men and us just ‘little city girls’ with no muscles. Mind you, we soon developed them!”

Land Girls with some Italian PoWs working in East Lothian.

Land Girls And Fund Raising

It’s clear from contemporary newspaper evidence that Land Girls were often involved in a variety of fund raising efforts. Under the title “Wings for Victory” thanks were given to “...the girls of Marygold Hostel, Dunbar and ... five girls from Slowbigging who gave up their leisure-time to get a concert up in aid of Wings for Victory. The five girls from Slowbigging deserve special mention, as they made up their own dances and rehearsed them without music.... the hostel members produced a very amusing sketch and one or two of the girls sang.”

On the 31st December, 1943, Land Girls at Oxwell Mains held a concert in East Barns school and the W.L.A. was praised by Mrs R. Hope for the, “...work they were doing in helping to win the war.” What followed was an “...attractive programme of songs, dances and sketches. a lucky draw and an auction and the concert ended with the singing of Auld Lang Syne and the National Anthem.” £20 14s was handed over to the Red Cross Prisoners of war fund.

Land Girls photographed at Dovecot market garden on the edge of Haddington.

Top left to right are Ella Ritchie, Ethel Bell and Cathy Cameron.

Bottom left to right are Alice ‘Betty’ van de Pear, Mima Benson and Celia?

[Note - both Ella and Cathy are shown in modern photographs above].

A poetic tribute to the Womens Land Army

Oats, Baggies and Barley Awns.

In Spring of 1943, so many years ago,

my friend and I left home,

East Lothian bound, while war was on

for tasks to us unknown.

With other girls we lived in style

in country mansion grand,

and, strange in boots and dungarees,

we toiled upon the land.

The work was hard, the hours were long,

the wages very small.

But, joking, laughing, singing,

we conquered over all.

Wearing brats we planted spuds

the drills seemed never-ending.

We paddled baggies, coiled the hay and

white-washed byres when raining.

Reaper and binder then held sway

at busy harvest time.

We gathered sheaves, eight to a stook,

we cursed the barley awn.

The golden days of leading-in,

all working as a team,

loading, forking, stacking,

the war a far-off dream.

The Harvest Home, to celebrate

the big house did us proud,

at kirns in nearby farms as well,

we revelled long and loud.

Howkin’ tatties, shawin’ neeps

oft frozen to the ground,

lowsen when the stars appeared

as shorter days came round.

Plucking fowls for festive fare

working Christmas, off New Year

mending sacks in draughty sheds:

winter could be drear.

Threshing grain, a stoorie job,

riddling tatties, what a grind,

then, time once more for spreading muck,

could Spring be far behind?

All aches and pains we soon forgot

at lively villages dances.

To Johnstone’s band we waltzed and reeled

the start of some romances!

The welcome into local houses

for friendly fireside chat

and farmhouse parties, sumptuous food,

I’ll ne’er forget all that.

Those friends of yore, so many gone,

a way of life now history

still fresh in memory lingers on;

fifty years! or yesterday?

Cathy Cameron, 1995,

Member of the Womens Land Army

1943-46

[A ‘brat’ was an apron of coarse sacking used

for carrying potatoes in

‘...paddled baggies’ means to thin turnips.

‘barley awns’ are the sharp ‘beards’ of barley.]

W.L.A. off to work by pedal power.

Helping with the harvest somewhere in East Lothian.

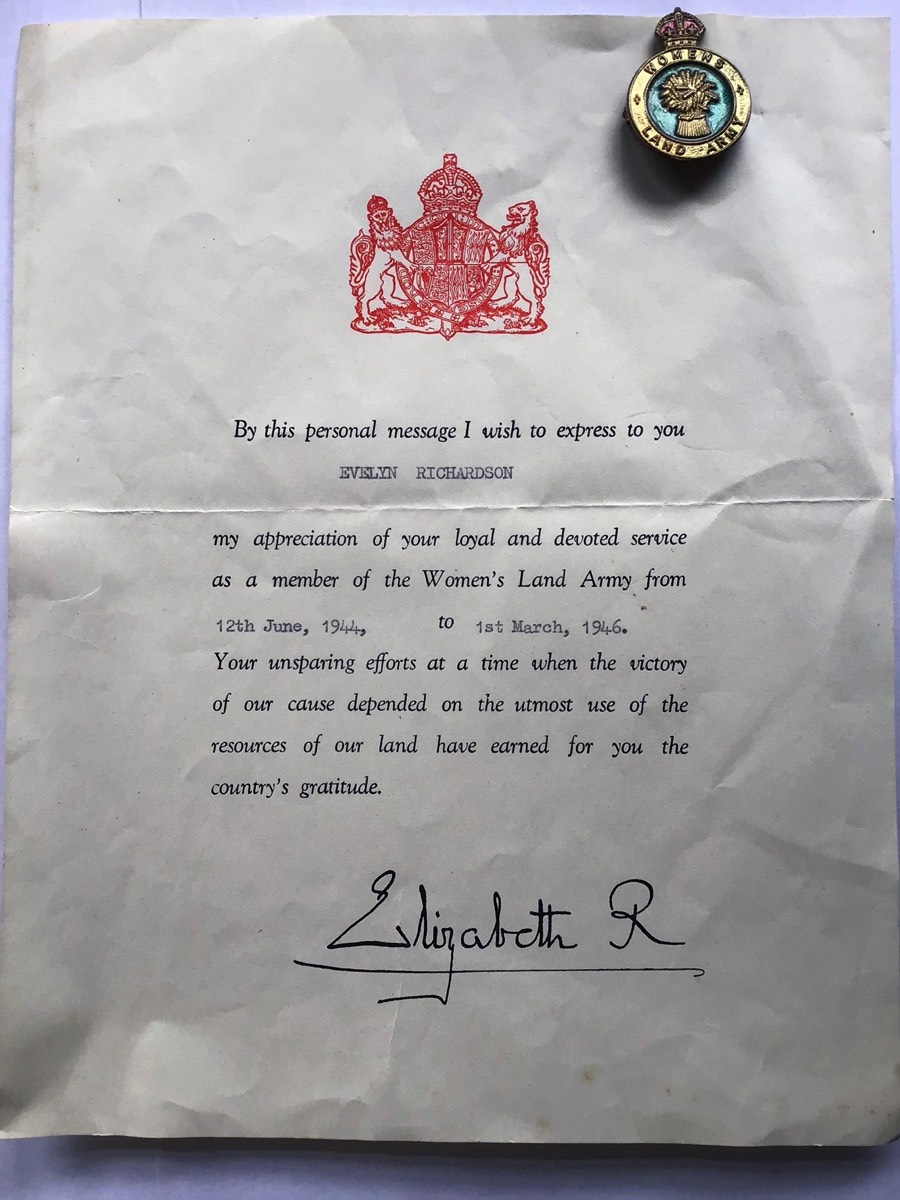

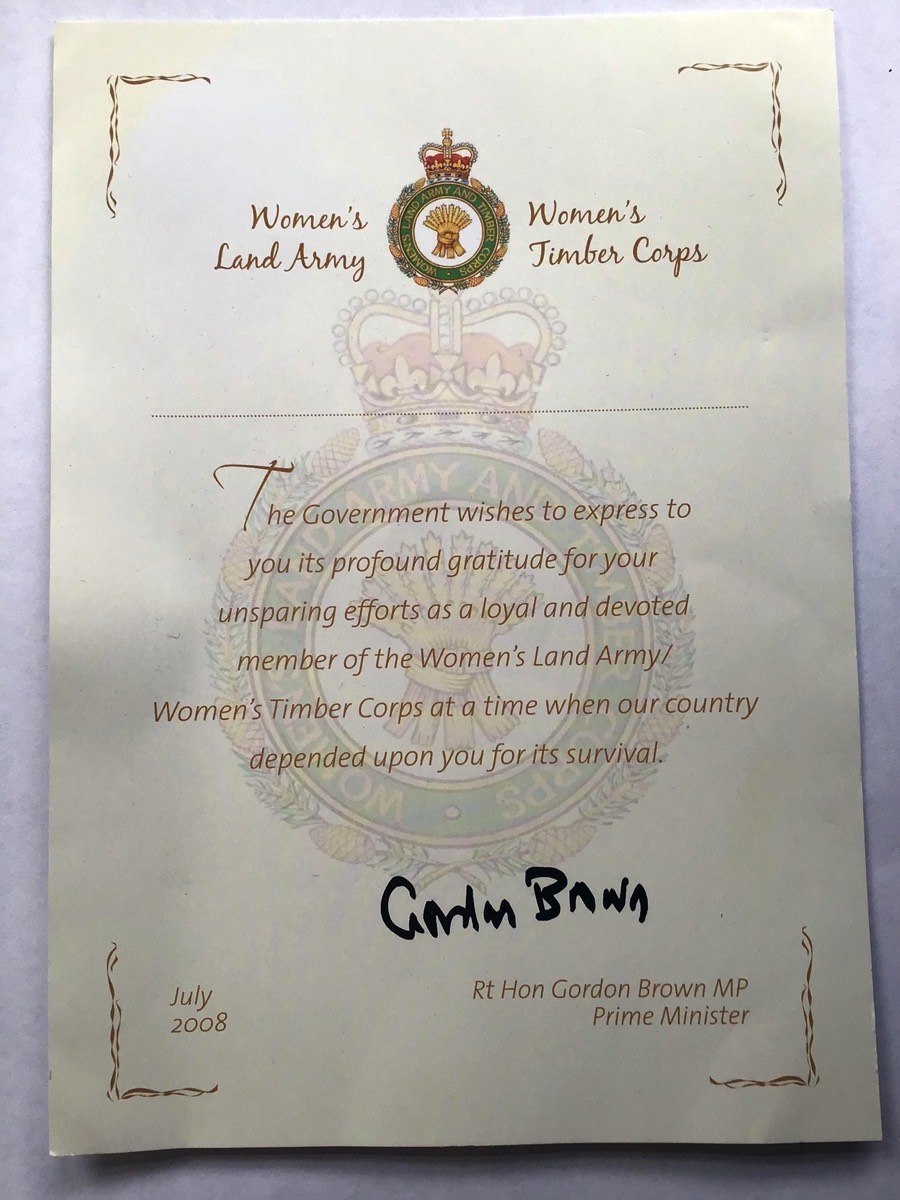

Royal recognition of Cathy’s contribution in the W.L.A.

Women’s Land Army Timber Corps

See section ‘Home Front: Timber Corps’ for an eye-witness account by Alison McLure who worked in the W.L.A.T.C. in East Lothian.